by Emma Ng | Aug 15, 2022 | Aotearoa Jewellery Triennial

Work in Progress: Raewyn Walsh

I don’t get to see Raewyn in person as much as some of the other makers — we live in different cities, and lockdowns and other Covid complications have made things harder. So it was really nice to be able to visit Raewyn at her place recently, and see the new body of work she’s been making for the first time!

When we first started talking, Raewyn and I spoke a little bit about her work as a whole — the pieces she’s produced in the past, and the threads that can be drawn through them all. One of the things that I admire about Raewyn’s work is that she has developed a recognisable language even as she continually experiments with new materials and ways of working.

Raewyn frequently works with natural materials — e.g. shell and bone — or mimics the forms of the natural world — e.g. her rock brooches. Recently she has begun experimenting with beeswax, which she has a small supply of each year from the bees kept in her backyard.

The wax is combined with pigment, essential oils, and damar crystals — which helps the wax harden. With the essential oils, the pieces invite us to experience them through a combination of our senses: sight, touch, and smell.

Raewyn intends them as pendants, and they are hollow. The idea that the wax encases a void is compelling, in a dark and mysterious way, calling to deeply ingrained human impulses. Raewyn introduced me to this idea of “l’appel du vide” (the call of the void) — the urge to throw yourself off a high place — which some people describe as a kind of death wish, and is sort of an unknowable human urge.

I think many of Raewyn’s works have this unknowable quality — they appeal to our human instincts on a ‘feeling’ level, even if we can’t quite put into words what the feeling or the appeal is.

— Emma

by Emma Ng | Jul 26, 2022 | Aotearoa Jewellery Triennial

Becky has been cutting out chain links from sheet aluminium, lots and lots of chain links. She described this slow process as feeling like “a kind of penance” — a gesture toward the debt owed to younger generations for the climate crisis.

The work that Becky is making is a continuation of her series about climate change. In some ways, the work combines her skills as a graphic designer and a jeweller. The pattern of blues and reds that changes across the work is drawn from data made freely available by Reading University.

The grid-like pattern references weaving. The textile industry was an early contributor to the huge changes of the industrial revolution, something Becky has written about before — and this connection intrigued me. For the shift to mechanised weaving represents not only a shift to more fossil-fuel-intensive way of working, but a loss of cultural knowledge held in hands: how to weave and the thousands of pattern languages that represented a continuous handing down from generation to generation.

In this way, historical examples of textiles provide us with so much information about the ways our ancestors made things around the world. Becky lent me a brilliant book called The Golden Thread – a global history of textiles told through a series of snapshots. As I mentioned in my post about Rowan’s lacework, there are several makers in this show whose practices reference textiles. I think it’s because textiles so naturally inhabit the show’s themes of cultural continuity, with practices like knitting and lacework — embedded as they are with historical knowledge held in hands and patterns, rather than speech.

— Emma

by Emma Ng | Jul 26, 2022 | Aotearoa Jewellery Triennial

It’s always fun to visit Neke at her home/studio in Ōtaki. For me as a curator, it’s interesting to see how different makers work. Some — like Rowan — are very methodical, planning every detail from the start (you have to, with lacework), while others — like Neke — work more intuitively, based on the materials and ideas that come along.

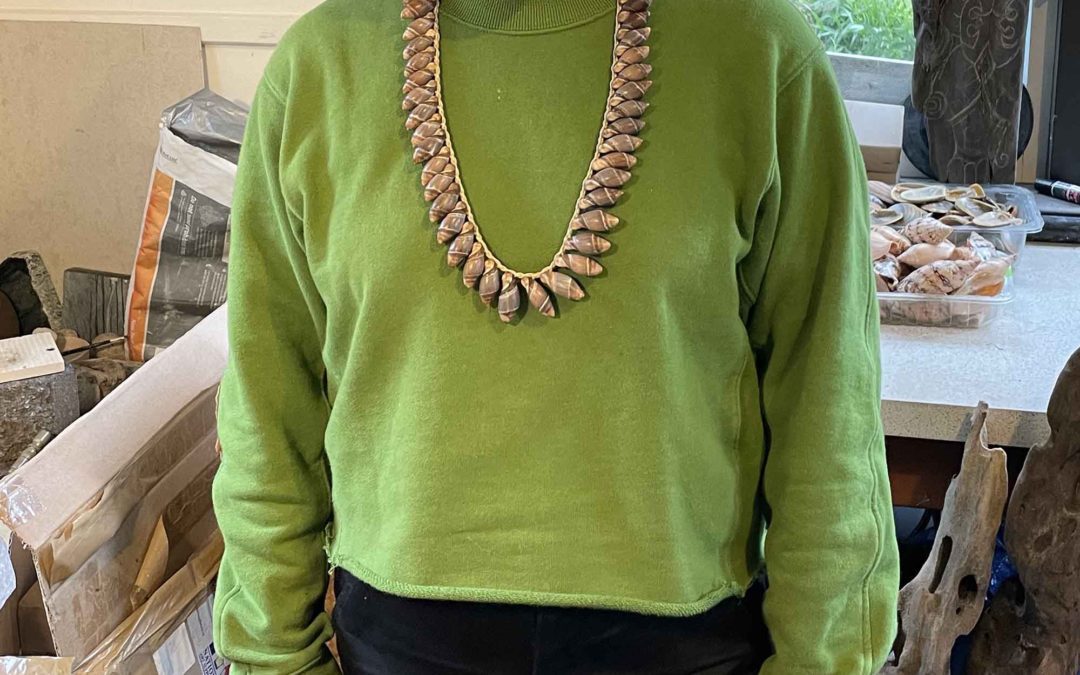

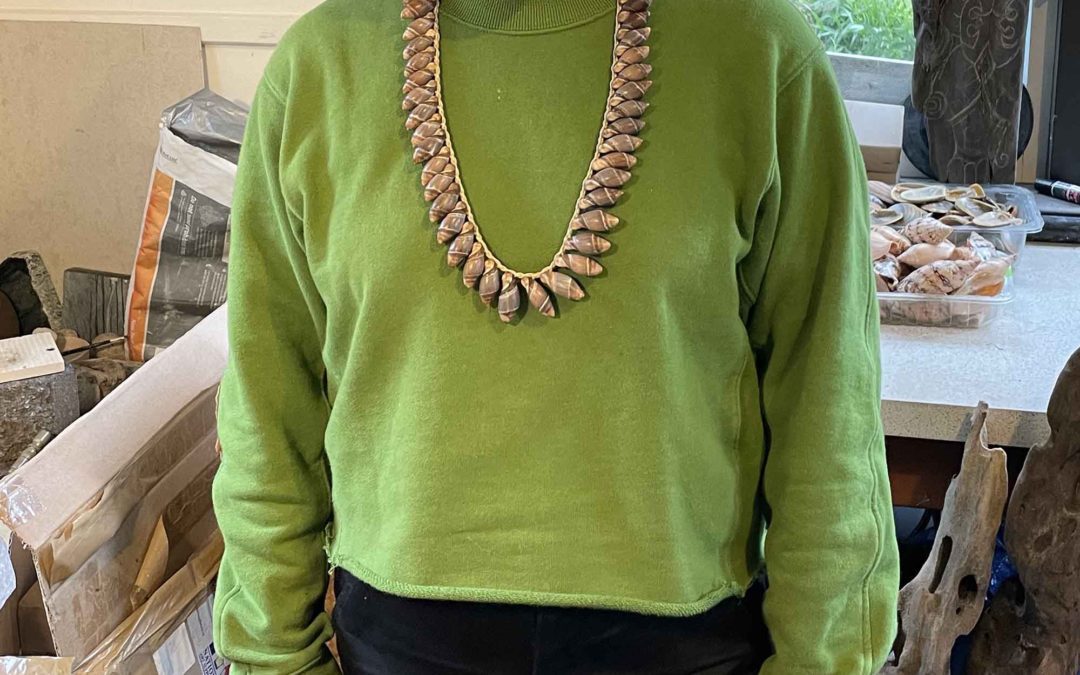

Most of Neke’s materials are collected during walks on nearby beaches — Ōtaki and Raumati. And if you know Neke’s work, you’ll know that she uses these materials from te taiao (the natural world) to channel pūrakau (stories) of the atua (deities) who shape te ao Māori (the Māori world/way of seeing).

For this exhibition, Neke is telling the story of Hine-Papaira, one of the creation sisters, and some of the main atua that descend from her, and their roles and relationships. We talked about how one of the qualities of Papaira is that she is curious, always pushing to the outer limits of her space, and looking, looking, looking. With that in mind, we looked closely at the beauty of the many shells Neke had collected, and appreciated the stories they might have to tell.

Neke and her partner Paula had also recently been at a wānanga with Matthew McIntyre Wilson — learning knots from him to create kupenga (nets). This has sparked some exciting new whakaaro (thoughts), about how this skill and material could be used in the work that Neke is creating for this exhibition…

— Emma

by Emma Ng | May 12, 2022 | Aotearoa Jewellery Triennial

Today I wanted to share a peek at what Rowan Panther is working on for this exhibition.

Rowan describes herself as a lace textile artist. She began by learning about bobbin lace making from influential lacemaker Alwynne Crowsen. Over time, Rowan began to consider how she might combine this European practice with her Samoan whakapapa – and many of her pieces reference breastplates, collars, and other forms found in Moana adornment.

Like Neke Moa, who is also making work for this exhibition, Rowan works with muka (harakeke fibre). The processed muka fibres are a glossy, luminous, cream-white. Although they are fairly strong, they have a visual delicacy, offset in Rowan’s work by pieces of silver, and brought into balance by the imposing scale of the finished pieces, and the inclusion of hard materials such as shell and wood.

This exhibition explores how makers reinterpret the ideas and techniques they’ve inherited, so including Rowan was an obvious choice. She spends a lot of time looking at books about lacemaking and taonga in museum collections in the lead-up to creating each series of work.

In the photo above, you can see some of the images Rowan has put up to refer to as she works. Included are photos of masi (FE000269), siapo (FE001420), lace (PC000331), and hiapo (FE000278) from Te Papa’s collections (the bits in brackets are the registration numbers, if you want to look them up on the Te Papa website. The three lace images are from a book called 100 traditional bobbin lace patterns by Geraldine Stott and Bridget Cook. These are intermingled with photocopies of native plants that Rowan has collected locally: Muehlenbeckia/Pohuehue, Kauri, and Kawakawa.

For this exhibition, Rowan wanted to try out a technique typically used to create lace borders. A design is woven through the border using ‘thick gimpwork’. Rowan is using this technique to pick out designs inspired by some of the plants that surround her in Doubtless Bay, Northland, where she lives and works.

I hope this whets your appetite for the finished pieces! Some of the other makers in this exhibition share an interest in textiles, so I’ll write a bit more about that connection in future posts, too. Stay tuned!

— Emma

by Emma Ng | Apr 15, 2022 | Aotearoa Jewellery Triennial

The label ‘biennial’ or ‘triennial’ marks out a different kind of exhibition. But in developing this one, I’ve been wondering: when is a triennial no longer a triennial?

The Aotearoa Jewellery Triennial is a new initiative developed by Makers101. It follows in the footsteps of the New Zealand Jewellery Biennial, which saw four exhibitions presented and toured by the Dowse Art Museum between 1993 and 2001.

In their desire to represent a moment, biennials and triennials usually go for breadth – they tend to be sprawling affairs with long artist lists. The Dowse’s Jewellery Biennials fit this model, with each iteration featuring anywhere from 13 to 25 makers. By contrast, this exhibition will include only six. So given the relatively small number of makers in this exhibition, what sets it apart from any given group show?

Jewellers in Aotearoa are already very connected to each other; exhibiting together fairly often. Even if more makers were included, the question of what sets this show apart would remain – as there are plenty of examples of larger group jewellery shows in Aotearoa that are not biennials or triennials. Many of these exhibitions have been facilitated by Peter Deckers and Makers101. Examples include exhibitions such as CHAINreaction, displayed during Nelson Jewellery Week in 2021, which featured 49 makers – all of whom had been involved in the Handshake Project over the last decade.

Instead of scale, I’d like to consider another quality of biennials/triennials more closely – the representation of a particular time and context. What is the context for this triennial? I talk about some of this context in the statement of intent for this exhibition – this is a time of great uncertainty, with forces like climate change and the pandemic having a huge impact on our lives.

The development of this exhibition has not been exempt from these conditions – it’s been a slow process, stymied by the Covid-19 pandemic. The pandemic has altered relationship between the local and international – a dynamic that typically underpins biennials and triennials – and exacerbated some of the difficult conditions that artists and makers in Aotearoa already experience.

Given these conditions, I think it is natural for us to question the sustainability of biennials and triennials, which are forms of exhibition making that can be incredibly exhaustive and exhausting. Even before the pandemic, biennials had begun to be criticised for their bloat and their touristic approach – at their worst, seen as vanity projects that touch down in cities and cultivate only superficial engagement with local conditions.

If a key quality of a biennial or triennial is to respond to or reflect its own moment, then this triennial needs to respond to the realities of being a maker in 2022. Everyone is tired. Everything is uncertain. It makes no sense to perpetuate an exhibition form that spreads resource and attention thin. Because the makers in this show are being asked to produce new work, the choice to focus on just six makers presents the chance to carve out some time and space for these makers to breathe, a chance to explore an idea, and create new work – with the provision of a decent artist fee, materials budget, and other kinds of support – thanks to Makers101 and Objectspace.

It is a struggle to decouple the idea of a ‘triennial’ from sheer scale. But here are my alternative aims for this exhibition:

- To represent impulses in the contemporary moment through six distinct practices.

- To give makers a chance to explore their ideas deeply, by offering time and support for the creation of new work.

- To create an exhibition that provides a ‘way in’ for new audiences to relate to contemporary jewellery/adornment practices, by situating them within wider culture and society.

image: Invitation to ‘Open Heart’, the first Jewellery Biennial, curated by jeweller Eléna Gee